American Samoa: Football Island

This story was originally published on Jan. 17, 2010. It was updated on Sept. 17, 2010.

There's a small community that produces more players for the NFL than anyplace else in America. It isn't in Texas, or Florida or Oklahoma. In fact, it's as far from the foundations of football as you can get.

Call it "Football Island" - American Samoa, a rock in the distant South Pacific.

How's this for a football stat? From an island of just 65,000 people, there are more than 30 players of Samoan descent in the NFL and over 200 playing Division I college ball. That's like 30 current NFL players coming out of Sparks, Nev., or Gastonia, N.C.

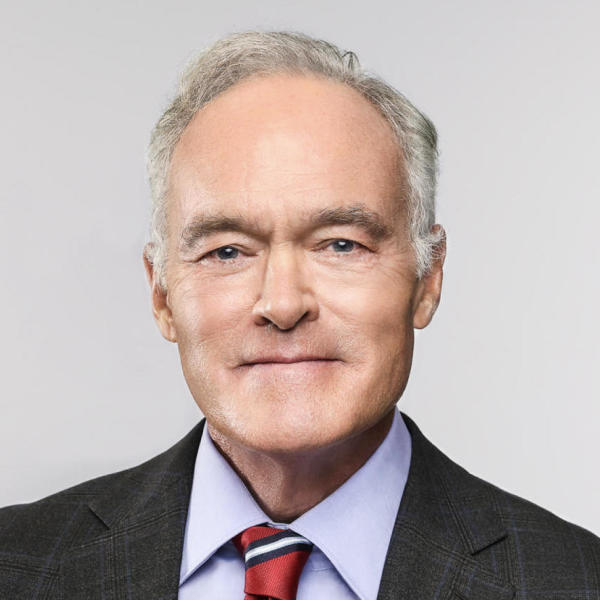

As we first told you last winter, "60 Minutes" correspondent Scott Pelley traveled 8,000 miles to American Samoa and found a people and traditions so perfectly suited to America's game - it's as if they'd been waiting centuries for football to come ashore.

Web Extra: Troy Polamalu

Web Extra: The Governor's Office

Web Extra: The Haka War Dance

In American Samoa, a football team warms up with the Haka War Dance - something that's been passed down for ages to teach agility to warriors of size and strength.

What coach doesn't wish he'd thought of that first? It turns out the South Pacific was raising football talent before there was football.

While Pelley was there, the island was getting set for its version of the Super Bowl - the High School Championship.

After a winning season, 16-year-old quarterback Tavita Neemia would lead the Samoana High School Sharks. His coach, Pepine Lauvoa, has a roster that mainland schools dream about.

"They're soft spoken, they're gentle," he told Pelley of his players. "But when they put on their equipment, they just become monsters. And they just want to go out and hit and hit and hit."

Web Extra: Scott Pelley Notebook

One 16-year-old player told Pelley he's 6 feet 5 inches tall. Another, 17 years old, said he's 6 foot 4 and a half.

"It looks like you've been hitting cars with this thing," Pelley said, holding a beaten-up football helmet, eliciting laughter from the players.

In the last five years alone, the island's six high schools have produced 10 NFL linemen. It's estimated that a boy born to Samoan parents is 56 times more likely to get into the NFL than any other kid in America.

The Samoan people are big. And big is beautiful, according to Togiola Tulafono, the governor of American Samoa.

Tulafono said it's not just size that makes the Samoans such great football players. His people come from a farming culture that prizes hard work, reverence and discipline. And he thinks that's why scouts and coaches are pulling out their atlases.

"I'm afraid most Americans back on the mainland would be hard pressed to pick this place out on a map," Pelley said.

"Yeah, it's not very visible," Tulafono agreed.

"It is a small dot on a big ocean."

"It is, it is," he responded. But nowadays Google helps a lot."

American Samoa is a paradise - clear seas and 80 degrees most of the time. It's a land that roared out of the Pacific in a volcanic eruption. Nearly 5,000 miles from California and way past Hawaii, it's the only inhabited American possession south of the Equator. Of the seven islands in the chain, the largest is just over 19 miles, end to end.

It was back in 1899 that the U.S. Navy sailed into this harbor and figured that it was perfect for refueling ships. The islands have been American ever since.

The Samoan people aren't exactly American citizens. They can't vote for president - but, on the other hand, they don't pay income taxes either. The capital, Pago Pago, has an American feel. Flag Day is the most important holiday and there's a tradition of sending kids into the U.S. military. But for all its beauty, American Samoa is not blessed with wealth. For the most part, Samoans make a living canning tuna. Two-thirds of the people are below the poverty level.

Tavita Neemia, the quarterback for the Sharks, has a typical family. His mom works at the cannery, and he'll need a scholarship to go to college. He and Coach Lauvoa make the most of what they have.

The high school football field, which Lauvao called the "Field of Champions," is short, rocky and unlined. The team doesn't have a locker room or a weight room, either. And yet three NFL players have come out of his school.

"How are you turning out NFL football players?" Pelley asked Lauvao.

"Determination," he responded.

Voc-Tech High School has one player in the NFL. But Coach Ethan Lake has no practice field at all, and no locker room. A rusted shipping container is the storeroom for his varsity team's busted, antiquated equipment.

"Everything that's in here, that we have gotten here in American Samoa, is actually donated," Lake said. "It's second-hand equipment. And it's actually equipment that would never be allowed to be used in the States."

"Coach, if you used some of this gear back in the States, you'd get sued," Pelley remarked.

"Definitely, definitely," he nodded.

For all its success, American Samoa has never had youth football until this year.

The NFL and USA Football are helping to start the program. But all of the players that came before started playing in high school.

USA Football

American Youth Football (AYF)

Samoa Bowl

June Jones Fondation

All Poly Sports

Aiga (Family) Foundation

It seems they do well despite the adversity. But getting cut up on lava rock and playing in sneakers without equipment are the keys to their success. Samoans are born big, but the island makes them tough.

This is a place where kids use machetes to do their chores. Come to think of it, its a place where kids do chores. Seventeen-year-old Aiulua Fanene does a day's work before school, under the direction of his father, David.

"He's cooking in this house. He's cleaning in this house. That is something that kids back on the mainland would not believe if they didn't see it," Pelley told David Fanene.

"That's how he's been brought up. Discipline…Obedience should be involved in this house and I am expecting my children to obey us," he said.

Aiulua stands 6 feet 5 inches tall and weighs 280 pounds. Arizona and Oregon State offered him scholarships. One day, he hopes to follow in the cleats of his brother, Jonathan Fanene, the defensive lineman for the Cincinnati Bengals.

"When you sent him to Cincinnati, did you give him any advice on how to live and how to play football?" Pelley asked Fanene.

"Well, I told him once you put on your football equipment, automatically you turn into a lion, turn into a lion that's chasing a deer to eat," he laughed. "You know what I mean."

"Play like a lion, but be a humble man," Pelley remarked.

"Be a humble man," Fanene agreed.

While humble, the Fanenes know the rewards of NFL success. Football has been very good to the family - Jonathan built them a spacious home back on the island.

From an island where the average income is a little over $4,000 a year, Jonathan Fanene is making more than $1 million in Cincinnati. Paul Brown Stadium, where the Bengals play, would seat everyone back in American Samoa, with 1,000 seats to spare.

"With the talent that we have, we have to take pride of it," Jonathan told Pelley. "Especially when you have the opportunity to come to the mainland, you got to take advantage of it."

Fanene is a defensive end who had a breakout season last year with six sacks. He's one of two Samoan-born players on the team, along with Domata Peko.

"The combination of size, and ability and speed, you know, that's kind of hard to find. Big dudes that can have nimble feet, you know, and are able to run and go sideline to sideline," Peko said.

The NFL's "Sunday Samoans" are hard to miss, with their vowel-laden names and trademark hair. The most famous is Pittsburgh Steelers all-pro safety Troy Polamalu. Born in California to Samoan parents, his name is on two Super Bowl trophies.

"What if there were 120 million Samoans, you know? How many Samoans would there then there be in the NFL?" Polamalu quipped.

"If there were 120 million Samoans, it might be the National Samoan Football League," Pelley told the football star.

Polamalu laughed. "That would be interesting, yeah."

He may well be the most versatile defensive player in the league - smart, fast and a hell of a hitter.

To a kid growing up in Samoa, Polamalu told Pelley, football is a "meal ticket."

"Just like any marginalized ethnic group, you know, if you don't make it to the NFL, what do you have to go back to?" he asked.

In addition to a meal ticket, the sport also provides an education. A lot of Samoans would never go to college if it wasn't for a scholarship with football.

"That's the beautiful thing about football," Polamalu continued. "It's allowed us to get an education. Football is something that comes naturally to us."

Football has never been more important to the island than right now, because this season there's been more than the usual trouble in paradise. The island may lose its tuna industry. One cannery, Chicken of the Sea, has left. And because the U.S. Congress wanted to help Samoa by imposing American minimum wage, Governor Tulafono is worried that the last cannery, Starkist, could look to other shores.

Tulafono said that some economists have estimated that 80 percent of the Samoan economy is wrapped up in tuna canneries.

"Eighty percent of everything that goes on around here," he stressed, "is dependent on the prescence of the canneries."

And they just lost one of those canneries on Sept. 30.

"What does that mean to you?" Pelley asked.

"Devastation," Tulafono sighed.

In the fall, there was natural devastation, too. The day before that cannery closed, the island was struck by an earthquake that led to something much worse.

When the shaking stopped, people traveling on one of the roads overlooking the ocean could see the water moving back to sea, and a few of them knew what was coming next.

It was a tsunami - the devastation recorded on a security camera until the power went out. The wave pushed inland for a mile, killing 34 people and washing away entire villages.

"When I heard the village that got hit, the first thing that came through my mind was my football players," Lauvao said. "And then, I found out 13 of my kids either lose their home or home damaged by the tsunami."

One of his kids who was hit by the disaster was quarterback Tavita Neemia. His home was damaged by the earthquake. With about eight weeks to go before the championship game, some thought they should cancel the season, but Governor Tulafono decided that football would cheer everybody up.

Nameeia's school, the Samoana High School Sharks, prepared to play the championship favorite Tafuna High School, featuring Aiulua Fenene. But in another blow in a cruel season, Nameeia's father died suddenly, just weeks after the tsunami. They decided the game would go on, but it was postponed to later in that day so that Nameeia could bury his dad.

"This kid is the leader on the team. And this kid has heart," Lauvao said of his quarterback.

Hours after the funeral, the Samoana Sharks and Tafuna High met for the last game of the season. Nameeia connected early and jumped out to a surprise 7-0 lead. The rest of the game was a contest of all-Samoan defensive lines. Ultimately, the Sharks won 7-6, their first championship win in 11 years.

When the clock struck zero, Lavuao looked for his quarterback, who was crying and hugging other teammates.

"I told him, 'This is for you. Your father is looking down on you, and he's very proud of you.' And I gave him a hug."

Nameeia responded, through tears, "I love you, coach."

That moment revealed the real reason why a community of 65,000 has so many players in the NFL. Turn's out it's not the size - it's the heart.

Produced by Pete Radovich