A jail that helps veterans heal their mental wounds

This article was originally published in The Crime Report.

A year to the day after his baby brother was shot dead in a Kansas prairie town, German Villegas' best buddy in Afghanistan, U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Michael J. Palacios, was killed by a bomb he'd been ordered to find and defuse.

"We were both on the list to search for explosives," Villegas recalled.

But it was Palacios who was ultimately dispatched that day in November 2012. "He got hit by a 200-pound IED," two months before both men were slated to go home, Villegas said.

Villegas returned stateside, a shattered man.

"My number-one goal was to get drunk and just try to forget everything," said the 23-year-old, who joined the Marines straight out of high school and spent five years in the service. Fired from the military police, he was shunted into what he calls "punitive duties" that had him cleaning up after battalion officers and picking up trash.

But the worst were the funeral details.

"(That) was the completely wrong thing for me to have to do," he continued. "Every time I did one of these funerals, I'm seeing these families crying. I became pretty good at compartmentalizing -- or so I thought."

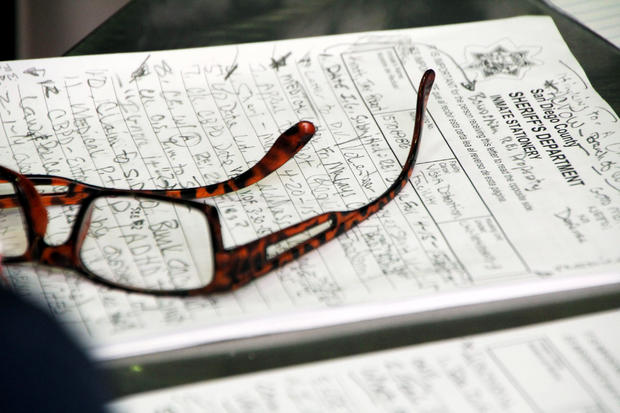

As he spoke, Villegas was sitting in the communal area outside an all-male cell block at a San Diego County Sheriff's Department jail, where he landed after being arrested for an assault on his fiancée. A few feet away, at the Vista Detention Facility, stood one of the deputy sheriffs, also a veteran, who asked to be assigned to that cell block. Just beyond that deputy was a Marine Corps retiree and correctional counselor who directs Vista's almost two-year-old Veterans Moving Forward Program.

One of a handful of such projects in the United States, the program makes available to convicted ex-military men and those awaiting trial -- including those like Villegas who've been diagnosed with mental illness -- counseling, peer-to-peer support and other amenities rarely extended to people behind bars.

Minutes before Villegas gave a visitor his take on what war extracts from combatants and innocents alike, he had queued up at a nurse's cart, where anti-psychotic and other prescribed drugs were dispensed to jailed veterans with mental illnesses and physical ailments.

Villegas' meds are intended to help him stave off anxiety, depression and the flashbacks, nightmares, hyper-arousal, hyper-alertness and exponential moodiness that are among the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Villegas says suchmaladies are likely what triggered his admitted episode of violence. Villegas, like so many other criminally charged veterans, had no history of illegal activity prior to military service.

"Jail is the last place I thought I would end up and the last place I thought I would find help, but this program has become a foundation that I can trust," Villegas said. "The moment I came here and saw those military flags on the walls, it brought me to tears. There's a brotherhood here ... and there are things here that I need to restore my mental health, to get whole again."

Jailed Vets, 10 percent of America's incarcerated population

There are no current figures for the number of veterans confined to state and federal prisons. According to the most recent statistics available from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, dating from 2004, they comprise 10 percent of the incarcerated population.

Aiming to serve them are the relatively few units such as San Diego County's (which, unlike most of the nation's jails, allows some convicted persons to serve their sentences in county jail, instead of state prisons, the result of a 2011 revamp of California's penal laws).

Generally, the veterans volunteer to be diverted to such units through special veterans-only treatment courts -- about 220 exist around the country -- that form another arm of a broad and growing strategy to keep as many criminally accused former military personnel as possible out from behind bars.

That strategy is being pursued as the nation grapples with how to balance citizen demands for public safety with efforts to pare incarceration costs, incarceration rates, and the risks that those released from prison will return to crime.

In that quest, veterans have emerged as a prime target.

For one thing, their service and sacrifice make it hard for would-be critics of "perks" for prisoners to scoff at programs aimed at incarcerated veterans' uplift, said Melissa Fitzgerald, senior director of Fairfax, Va.-based Justice for Vets.

Her organization, an offshoot of the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, trains and certifies judges, social workers, law enforcement officers and related criminal justice professionals in the nation's drug courts, mental health courts and veterans treatment courts.

"Our veterans, including the ones struggling to get on their feet, served us," said Fitzgerald, a judge's daughter and actor who spent seven years playing Carol on NBC's "The West Wing" before signing on at Vets for Justice.

"They deserve our support and the opportunity to fight for their personal freedom. That's something that most of us can agree on."

Military-Style Discipline

Even in civilian life, veterans often follow a military-style discipline, regimen and routine. That capacity to heed the rules -- at least in certain settings -- lends veterans-only units a relative peace and day-to-day manageability not typically seen among the general population of incarcerated persons, according to the professionals who have worked with them.

"Generally, veterans have a somewhat higher level of education, at least a GED or high school diploma," said social worker Christine Brown-Taylor, the San Diego County Sheriff's Department's re-entry services manager. "They're trained in a skill. Some have college or college equivalency. These things help."

Glendon Morales, the correctional counselor occupying that un-walled desk in the Vista facility's communal area, agrees.

"Anybody who joins the military has a certain determination," he said. "If you made it through boot camp, that, in itself, was a major accomplishment. The idea is to get them back to that place, get them back to a mentality of accomplishing an assignment ... Their rightful place is not sitting in here, just being locked up."

San Diego County's unit is situated in Vista, 40 miles north of San Diego. It is modeled after the City and County of San Francisco Sheriff's Department's Community of Veterans Engaged in Restoration (COVER) project, which launched in 2010 in San Bruno, CA.

San Diego 'Vet Modules'

But the San Bruno veterans unit has accommodated fewer veterans than has San Diego County's.

So far, at Vista, where the oldest veteran inmate fought in the Korean War, roughly 270 veterans have been funneled through what jail officials refer to as "vet modules." The two adjoining modules accommodate 64 inmates, 32 in each module -- out of a countywide system that handles about 85,000 pretrial and convicted inmates a year.

Vet module participants can get an extra pillow or extra mattress. Flat screen TVs are bolted to cinderblock walls of units also adorned with renderings of the Statue of Liberty, the Stars and Stripes, and flags from the U.S. military's five branches -- all painted by prisoners or correction officers who themselves formerly served in the military.

There's a makeshift library of books, movies and videogames; an X-box; chairs, instead of metal stools, for seating; a soda vending machine, microwave oven and morning coffee; and a computer for checking email and conducting research.

The module's "reading legacy" project videotapes fathers as they read children's books, and mails those recordings to inmates' offspring.

"It's to create a better bond," said inmate Clyde Johnson, 50, whose beige, jail-issued uniform designates him as a stipend-earning inmate who helps lead one of the vet modules.

The module's inmate cells are unlocked for most of the day. Community volunteers regularly steer the veterans through yoga exercises or a 15-minute silence-and-sound therapy meditation.

"Breathe into your heart," a volunteer teacher told veterans reclining in chairs or bunks of their unlocked cells during one session. "Sit up on the bed or lay on your back. Try not to fall asleep."

She enlisted a veteran inmate to, on cue, sound the cymbals in the dimly lit room.

Also, in the modules, there's one-on-one counseling, group therapy, and meetings sponsored by Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous. A caseworker runs part of that programming; Vista's staff psychologist runs another part. The jail contracts a psychiatrist who is on call and arrives for standing appointments and for medical emergencies.

There are mandatory classes in anger management, overcoming drug and other addictions, parenting and grandparenting, holding down a steady job, succeeding in college, and corralling a crew of right-living friends, among other skills.

Correctional counselor Morales, who is working toward his master's degree in social work, teaches a National Institute of Corrections course, based on cognitive behavioral therapy, titled "Thinking for a Change."

Community volunteers and deputies run other courses. So do those designated inmate-leaders whose khaki-beige uniforms stand out in a sea of navy blue inmate garb emblazoned with "S.D. Jail."

Ronald Holt, 55, wears blue.

Holt was sentenced to 14 months in county jail for stealing a neighbor's generator -- "even though I gave it back," he said.

"The problem with my mental health and my learning disability is that it can be very hard to find real work," said Holt, who spent two years in the U.S. Air Force.

He has PTSD -- though that, he believes, resulted from a head injury sustained after he fell off a roof in 1983. In 2000, doctors at the California Rehabilitation Center, a state prison in the city of Norco, where he served a prior prison sentence, diagnosed him with bipolar disorder, whose symptoms include extreme emotional highs and lows; schizoaffective disorder, whose symptoms include hallucinations and delusions; and anxiety. Daily, he takes four different medications to quell and contain those diseases.

The streamlined mental health care, along with the vets module menu of activities, makes a big difference to Holt.

"Before I got here, I had lived through 10 years of all kinds of hell," he said. "The change from here to there is 360 degrees. I have hope now."

Lt. Mike Nichols, of the county's sheriff's department, is one of eight officers who volunteered to stand guard and otherwise work in the vets modules. All eight also are former military men.

Nichols believes that the success of the approach is reflected in the unit's atmosphere, which bears little resemblance to the charged tension of most jails.

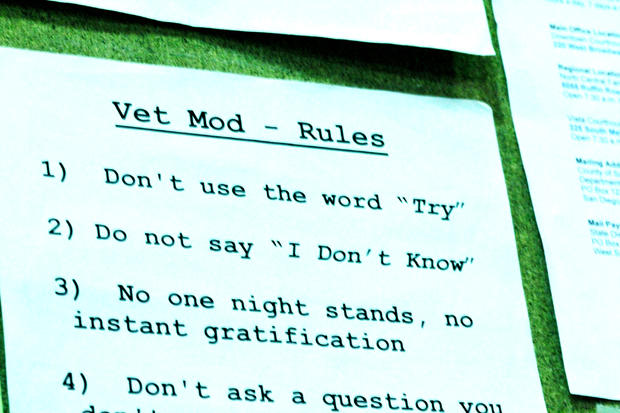

"We've not had any big disagreements, no fights, [fake] illness issues, or disciplinary issues where they tear up the cells, write on the walls," Nichols said. "They follow the rules, which are strict."

Those who break the rules are dealt with summarily. Some 28 inmates have been booted from the program since it launched, said counselor Morales, who spent 24 years as a Marine.

Teaching Tolerance and Problem-Solving

To a group of nine veterans who, in spring 2015, were on Day 1 in the vets module, Morales was plain and upfront about the rigors of his program.

"Everybody here will room with a person of the opposite race," Morales said.

He paused. Noticing a twenty-something whose fidgeting, shuffling feet and vocal outbursts suggested he was in psychiatric crisis, Morales sent him for a medical evaluation.

(His bunk would be waiting for him, unless he required a different kind of triage, Morales told a visitor later.)

Morales continued addressing the newcomers: "We teach tolerance here. We teach problem-solving, how to communicate and get rid of biases. If you can't work on those things, you do not belong here. Our main mission is to have you never come back to jail.

"If you think you want to come back to jail, let me know now."

Not one of the newcomers spoke up.

The Toll from Iraq and Afghanistan

Based largely on U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs data, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has reported that about 18.5 percent of returning Iraq or Afghanistan veterans have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder or depression. Some 19.5 percent self-report a traumatic brain injury.

The data also show a more disturbing figure, some observers said. According to Veteran Affairs (VA) analysts, half of returning military personnel who are estimated to need mental health care search for it; and half of those who get care do not get adequate care.

But so far, not even the federal government has an exact profile of veterans' physical and mental health. According to a 2007 VA report, cases of mental illness among veterans getting care from the VA surged 58 percent between June 2006 and June 2007, from 63,767 to 100,580 cases. Their diagnoses included PTSD, drug and alcohol addiction and depression.

It bears noting, however, said Thomas Berger, executive director of Vietnam Veterans of America's Veterans Health Council, "that the veteran universe is almost 22 million [people], of which only about 30 to 35 percent utilize the VA."

Berger, a Vietnam veteran, who has served previously as the Health Council's senior policy analyst for veterans' benefits and mental health, has testified before Congress, sometimes rolling out examples of what he describes as the VA's piecemeal parsing of mental illness among vets. Among those examples is this one: As many as 460,000 Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans--out of 2.8 million veterans of those incursions--have diagnosed or undiagnosed PTSD.

Units Around the Nation

While the exact figures regarding veterans' mental health remain unclear, the number of jail and prison programs for incarcerated veterans with and without mental illness barely responds to the need, according to a range of criminal justice and mental health advocates and policymakers. The most prominent among those units range from a 130-bed unit at Washington Department of Corrections' Stafford Creek Corrections Center that opened in August 2015; to a 16-bed unit at the Muscogee County Jail in Columbus, Ga., opened in April 2012; to a total of 400 beds across five Florida Department of Corrections prisons opened on Veterans Day 2011. In October 2013, a 28-inmate unit opened at the Erie County Holding Facility in Buffalo, N.Y., home to the nation's first veterans treatment court.

There are no similar units for incarcerated women veterans.

But while the number of such units may be inadequate to address the need, they represent what some see as a promising departure from the past.

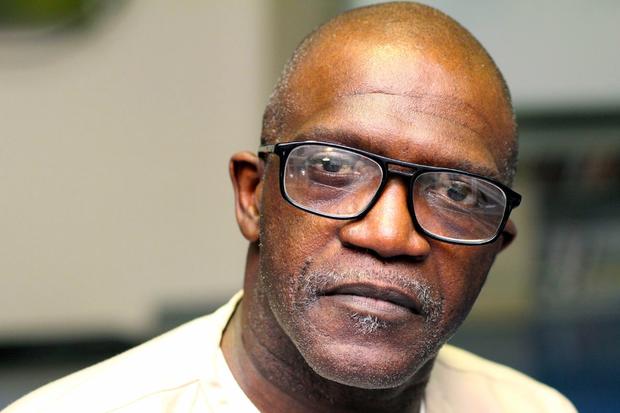

Traumatized veterans of Vietnam and earlier conflicts wars were dismissed as "shell-shocked" and received nominal, if any, mental health care, said Glennis Goodwin, 61, one of the beige-uniformed inmate leaders at the Vista facility.

The American Psychiatric Association officially added brain- and behavior-altering PTSD to its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980. Research on the psychological and psychiatric impact of traumatic brain injury (TBI) -- a hallmark harm of the current wars and weapons of warfare -- is just beginning to ramp up, observers said.

"Our fellow Americans figured that somehow, magically, we would just get over it all," said Goodwin, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 1987 but accepted "the reality of that" in 2003.

"I spent 16 years and nine months in the Army," said Goodwin, also diagnosed with PTSD. "In 1987, the Army asked me to retire because I choked an ensign ... despite my years of service and my medals for exemplary conduct and what not. It was part of a downward spiral.

"We soldiers drank our troubles away, we fought, we had good camaraderie. And when I came back home, I got spit on and talked about all because I went to a place where my government told me I had to go ...

"Much of what we suffered got swept under the rug. I have been such an angry man. I've sold drugs -- and been in solar-energy building construction -- and I've fought police. I wound up in here. Finally, I am taking the lesson. I'm betting that something deep in my inner man has changed."

Other inmates said being in a veterans-only unit has been cathartic -- even if the future, beyond incarceration, presents some critical unknowns. Will the mental health and other medical treatment they get outside jail be the same quality and consistency as inside? What of jobs, housing, schooling?

The vets module is supported by veterans organizations and other non-profits whose members provide mentoring, connections that might lead to employment, housing and so forth, said Morales, vet module director.

"We have our successes," he continued. "We have a lot of individuals who are out (and) working who call me every month and say 'I have a job, I'm in school ... ' Getting out of jail is one thing. But if they don't have help, if they run into trouble, what then?

"Community involvement helps make the difference. We need much more of that."

Imagining a Better Future

The San Diego module has already made a difference to German Villegas.

Being incarcerated alongside other veterans, hearing their encouragement and having their support, has helped him imagine a better future for himself, his fiancé and their one-year-old daughter.

Over and over again, he sketched that baby in pencil on drawing pads donated to the vets module.

The sketches are pasted on his cell's cinderblock walls.

"I am light years from where I started when I got here," Villegas said. "I felt abandoned by a lot of people and by the military. When you think you are setting out to do something great, something bigger than yourself, by joining the military and you get home from Afghanistan in the middle of the night in a place where no one is there to greet you, you realize that people have very short memories.

"I got no post-deployment mental health assessment. I'd wanted to go to aviation school but I found out the GI bill doesn't cover that ... Nevertheless, being with these veterans has helped me get back to who I was before ... I'm part of that community. I plan to take that confidence with me when I leave here."

Inmate leader Goodwin, listening to Villegas, emphatically echoed that sentiment.

Calling the vets module a "collaboration," he said. "I learn from the young cats. I try to apply that to my life. I suspect that they do the same when they check out us older cats. We all vibe off each other. We root for each other. We are trying to stay the course."

That's the kind of attitude San Diego County Sheriff William Gore aimed to engender when he and his staff rejiggered existing funds -- the San Francisco Sheriff's veterans program launched with a special government grant -- to create the veterans programs, jail officials said.

"I've been in corrections 27 years," said Lt. Robert Mitchell, Gore's lead administrator. "And for most of those 27 years, nobody talked about what offenders who are veterans face.

"It was: they got arrested, they got sent to jail or prison. They got out and often committed another crime. Our vets module is getting us where we want to go. It's baby steps, but it's huge steps."

Katti Gray is a contributing editor for The Crime Report and 2014-15 Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Journalism Fellow.