48 Hours: How much weight should a confession carry?

LAKE COUNTY, Ill. -- How much weight should we give to confessions?

We know people confess falsely, sometimes very convincingly, but how do we know which ones to believe? What if the confession doesn't match the evidence? These are questions raised by the disturbing case of Melissa Calusinski.

It is possible that this 28-year-old woman could spend the next 25 years in prison, not for what she did, but what she said she did. While she confessed to murdering a child, there is considerable new evidence to support her innocence. What and whom to believe?

On Jan. 14, 2009, Melissa Calusinski, 22 at the time, was working in a day care center in Lake County, Ill. when a 16-month-old child, Ben Kingan, suddenly became unresponsive in her care and later died. There were no unusual marks on the child: no cuts, no deep bruises, nothing to indicate any abuse. But according to the pathologist who did the autopsy, Ben Kingan did have injuries inside the brain that were inflicted on the day he died.

There were two women in the room with Ben when he became unresponsive, Melissa and another aide, Nancy Kallinger. Both women were interrogated by police. Nancy told police that she saw nothing happen to Ben in the room. Melissa told them the same thing.

Over 70 times Melissa told them she did nothing to hurt Ben, but after six hours in a police interrogation room, without a break to go to the bathroom or to get a drink, her story began to change.

She told police that there may have been an accident. That wasn't enough for investigators, and they kept questioning her. After three more hours of intense questioning, Melissa finally told the story that the investigators were waiting for: she confessed to throwing the child on the floor out of frustration.

And she didn't stop there. After confessing once, she went to another police station and told the same terrible story. Melissa Calusinski was charged with murder, and although she quickly recanted, it was too late.

At trial in November 2011, the state's medical witnesses told the jury that the head trauma that Ben Kingan suffered happened on the day he died and had to be caused by Melissa. Defense medical witnesses disputed that, saying the child had suffered a head injury several months earlier that left him vulnerable to any minor impact.

In the end, it was the state's arguments and Melissa's taped confession that convinced the jury: they convicted Melissa Calusinski of murder. She was sentenced to 31 years in prison.

That would be the end of it if not for Melissa's father, Paul Calusinski. Believing in his daughter's innocence, he convinced a newly-elected county coroner, Thomas Rudd, to re-examine the evidence. As Rudd later related, "I could not believe what I was seeing, because it was the exact opposite of what was written. So, I had my head spinning."

What took Rudd by surprise was the discovery of clear evidence of an earlier injury in the child's brain. That injury, according to Rudd, occurred weeks or even months before the child died, possibly before Melissa Calusinski worked at the day care center.

It was crucial evidence that was somehow missed by the pathologist who did the autopsy. Rudd now believes that it was the earlier injury that set into motion the events that led to Ben Kingan's death. When Rudd confronted the pathologist, Dr. Eupil Choi, with his findings, Choi admitted he made a mistake and even signed an affidavit to that effect.

Later, at the request of the State's attorney, Choi sent a letter saying that his error would not have changed his testimony at Melissa's trial.

Still, you might think that this error on the part of the state's star witness would cause the Lake County State's Attorney, Michael Nerheim, to take another look at the conviction. So far that hasn't happened, in large part because of Melissa's confessions.

Did she truly confess? Her attorney Kathleen Zellner says no. According to Zellner, Melissa Calusinski's confession, that followed nine hours of a relentless interrogation, doesn't match the evidence. If she did, in fact, throw the child in anger on the floor, why is there no injury or bruising on the toddler's scalp or body? When first prodded by police, Melissa takes a doll and throws it down face first. Ben Kingan's injuries are all on the back of his skull.

There is another factor that should be considered: Melissa's ability to understand what was happening in the interrogation room. Her records indicate a very low verbal IQ of 74 which means she has difficulty expressing herself and understanding others. Did that play a part in her confession?

Finally, there is this: according to the Innocence Project of New York , more than 60 percent of those exonerated by DNA tests in homicide cases first confessed -- falsely.

With impartial, medical evidence supporting Melissa Calusinski's innocence, how much weight should be given to her confession? It's a troubling case.

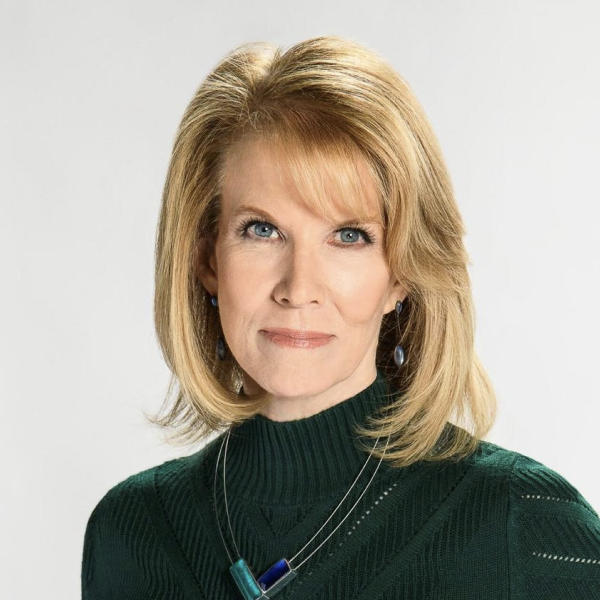

Erin Moriarty is a "48 Hours" correspondent. She investigates the Melissa Calusinski case Saturday at 10 p.m. ET/PT on CBS.