A recent history of FIFA scandals

GENEVA --The arrest of several top FIFA officials in Switzerland on corruption charges on Wednesday is only the latest in a long string scandals to plague the governing body of the planet's most popular sport.

FIFA President Joseph "Sepp" Blatter has been dogged by accusations of corruption and bad behavior since his first election to the position 18 years ago.

While officials did not arrest Blatter along with many of his top executives, New York Times reporter Michael Schmidt told "CBS This Morning" that he could still get swept up in the larger investigation.

"I don't think he's in the clear," Schmidt said.

Investigators are likely to wait to see what comes of the indictments of these senior FIFA officials, and later "look back and assess and see who they can go after," Schmidt said.

Blatter has never been directly implicated in personal corruption, but FIFA has often seemed relaxed about wrongdoing linked to senior officials.

The Swiss-born soccer executive now has to manage the worst crisis at his organization while also standing for reelection on May 29, in a vote that he has been expected to win easily.

Ahead of Blatter's bid for a fifth term, here are some of the ways soccer's governing body has earned its reputation recently.

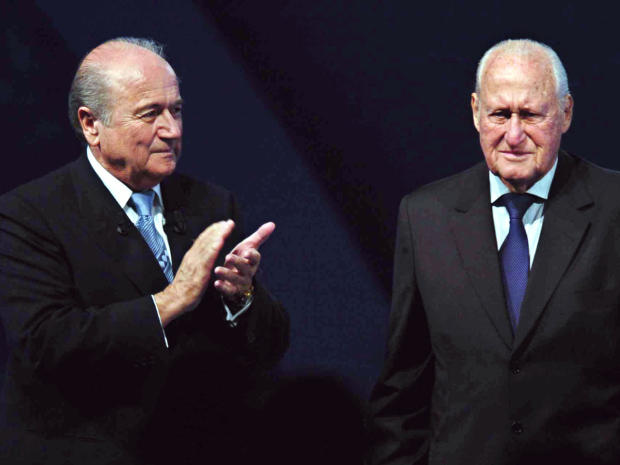

Joao Havelange

The former FIFA president, whom Blatter served under as a deputy and immediately followed into the head office, was forced to resign as honorary president in 2013 over a World Cup bribery case.

In addition to being forced to resign from FIFA, where he was president from 1974 to 1998, Havelange also had to resign from the International Olympic Committee, where he had been its longest serving member, having been on the board from 1963 to 2011.

The case that led to Havelange's resignations involved millions of dollars in kickbacks from World Cup contracts marketed by the ISL agency, which collapsed into bankruptcy in 2001.

ISL was created in the 1970s and helped fuel the boom in sports marketing, while also working closely with the IOC.

Havelange, and his former son-in-law Ricardo Teixeira were guilty of "morally and ethically reproachable conduct," a judge wrote in the verdict for the case.

Payments attributed to accounts connected to Havelange and Teixeira totaled almost $22 million from 1992-2000.

Blatter blocked legal efforts to reveal to the public who took kickbacks, which Switzerland's supreme court resolved in 2012. However, FIFA ethics judge Joachim Eckert ruled in April 2013 that Blatter's action "may have been clumsy" but was not misconduct.

It reinforced a view of many FIFA watchers: While not personally corrupt, Blatter is pragmatic about the morals of those whose support and votes he has needed.

1998 Election for FIFA President

A key turning point to understanding FIFA's modern history and Qatar's influence.

After 24 years of Joao Havelange's presidency, FIFA member federations had a clear choice in choosing his successor.

Sepp Blatter was Havelange's long-time top administrator who intimately knew FIFA's culture. He had Havelange's support and use of an airplane from the then-Emir of Qatar, according to author David Yallop's 1999 book "How They Stole The Game."

Lennart Johansson, a FIFA vice president from Sweden, promised financial transparency. He was backed by Europe and Africa and seemed likely to get more votes.

Mohamed bin Hammam of Qatar was then a FIFA executive committee member and key campaigner for Blatter.

Before the vote in Paris, intense late lobbying in hotels included widely reported offers of $50,000 to African delegates.

Blatter won 111-80, enough for Johansson to concede defeat before a second-round run-off.

At his victory news conference, Blatter dismissed questions of corruption, though he has since referred to reported vote-buying at the Meridien Montparnasse hotel.

"I will maintain that I was not there so it couldn't be me," Blatter said during his 2011 election contest -- against Bin Hammam.

The Qatar 2022 World Cup

The FIFA executive committee's choice of Qatar as 2022 World Cup host was the explosive event of Blatter's third term and dominated his fourth. Cases involving unethical behavior by some voters are still open.

Few think Blatter voted for Qatar, whose victory raised Bin Hammam's status six months before the 2011 FIFA presidential election.

Still, Blatter's reputation suffered. The 2018-2022 bidding contests showed a culture of entitlement and disregard for rules by some executive committee members which had festered on Blatter's watch.

An undercover sting by British newspaper The Sunday Times revealed the corruption that defined the bidding contests won by Russia and Qatar.

The 24-man executive committee of 2010 is now largely discredited: A life ban for Bin Hammam, shorter bans for others, some resignations to avoid FIFA sanctions and many allegations that were unproven.

Qatar has retained its 2022 hosting rights after FIFA declared that an internal ethics investigation judged that wrongdoing by several bid candidates did not influence the results.

However, the American lawyer who led the investigation, Michael Garcia, disputed the official findings that FIFA made public.

Garcia said the official line taken by FIFA on the investigation had "numerous materially incomplete and erroneous representations of the facts and conclusions" in his work.

Qatar itself has also come under intense scrutiny recently for the harsh treatment of foreign workers building infrastructure necessary to host the Cup.

2011 Election for FIFA President

Bin Hammam was boosted by Qatar's win and tired of waiting for old ally Blatter to leave. He ran for the presidency in 2011.

Blatter first promised European voters, then all FIFA members in a manifesto letter, that he would certainly stand aside in 2015 if he won.

In a tight race, 35 votes from the North American confederation seemed key.

Blatter pledged $1 million of FIFA money -- a gift now barred by election rules -- at CONCACAF's assembly one month before polling.

The next week, Bin Hammam went to Trinidad to meet Caribbean delegates who were offered $40,000 cash per country. Some of them blew the whistle to CONCACAF secretary general Chuck Blazer, an American smarting from the loss of World Cup hosting to Qatar.

The ensuing bribery scandal saw Bin Hamman withdraw days before the vote, then suspended by the FIFA ethics committee.

Bin Hammam told reporters at the time the suspension is "unfortunate but this is where we are -- this is FIFA."

"I should have been given the benefit of doubt but instead, I have been banned from all football activities," he later wrote on his official website.

Blatter was re-elected unopposed and Bin Hammam, who suspected complicity in a plot to entrap him, never returned to FIFA.

2014 World Cup in Brazil

While the last World Cup drew record ratings and revenue, there were numerous questions surrounding the tournament about worker deaths, corruption and inequity.

The 2014 tournament cost Brazil more than $11 billion to put on, and numerous Brazilian politicians and businessmen were found to have used some of that money for personal gain.

"Is there corruption in the Cup? Of course, without a doubt," said Gil Castelo Branco, founder of a Brazilian watchdog group in 2014. "Corruption goes where the money is, and in Brazil today, the big money is tied up in the Cup."

Thousands of people took to the streets of Brazil to protest the amount of money spent on the games, saying important state institutions like schools and hospitals were not benefiting from the massive amount of money flowing around the tournament.

World Cup Ticket Scams

As CONCACAF president since the 1980s, Jack Warner was formed in the Havelange era and allowed free rein by Blatter.

Warner's interest in World Cup match tickets -- often a FIFA currency to gain and retain support of favored officials -- peaked when his native Trinidad and Tobago qualified for the 2006 tournament in Germany.

His family-owned travel agency monopolized tickets intended for Trinidad fans. A confidential audit showed Warner's family profited by more than $900,000.

However, a FIFA investigation blamed one of Warner's sons and decided it had no authority over him. FIFA merely expressed "disapproval" of Warner in the case.

Warner's FIFA executive committee colleague Ismail Bhamjee of Botswana was caught in a British newspaper sting selling 12 tickets for England vs. Trinidad and Tobago at triple the face value.

Bhamjee, who was serving out his mandate and had little influence, was sent home by FIFA and later resigned.